'Structures and Styles' of Hartford Architecture

This article, by Kevin Flood, first appeared in the Journal Inquirer newspaper of Manchester on April 14, 1989.

"Structures and Styles: Guided Tours of Hartford Architecture" was out of print in 2010 but available in some public libraries.

So, you think you know every square inch of Hartford.

All right, where's Little Hollywood?

Hint: It's in the west end off Farmington Avenue.

Give up? It's a row of brick apartment buildings along Owen Street, supposedly given its nickname as a tribute to the beautiful young women who moved in there when it opened in the 1920s.

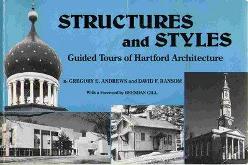

Stop to look at the buildings some day, and you'll notice their unusual mix of architectural styles—one has a slightly Moorish design while another echoes the Tudor Revival. Gregory E. Andrews and David F. Ransom throw the spotlight on Little Hollywood and 500 other examples of Hartford architecture in their book, “Structures and Styles: Guided Tours of Hartford Architecture.”

Published by the Connecticut Historical Society and the Connecticut Architecture Foundation, “Structures and Styles” highlights everything from downtown's Old State House to the trendy Comet Diner on Farmington Avenue, from pressed brick apartment buildings in the South End to Gothic churches in the North End.

While the book covers all of the expected landmarks, like the Colt Armory and the Travelers tower, its ultimate value lies in the attention it lavishes on dozens of lesser-known and even obscure buildings.

“One of the things we hope to accomplish is to give the reader some awareness of buildings that he's been walking by for years but just hasn't looked at,” Ransom said in a recent interview.

Those brick offices with the unusual twin towers at the corner of Elliott Street and Wethersfield Avenue, for instance, form the edifice of a 100-foot-deep trolley barn built in 1903 for Hartford Street Railway Company. South End residents of the 1940s knew the barn as an arena for boxing matches and dances.

Downtown, on Market Street, St. Paul's Church squats in the shadows of Constitution Plaza and Main Street's former department stores, the only evidence left of the poor but vibrant immigrant community that once occupied the city's riverfront.

And on Washington Street, situated among car dealerships and nondescript state offices, sits the Samuel N. Kellogg House, a relic of Washington Street's mid-19th century glory days as “Governors Row.” Mansions lined the street then, with giant, leafy elm trees shading them in the summer.

Andrews and Ransom pull buildings like those out of Hartford's landscape, providing a photograph of each one and a few paragraphs outlining its history and architectural style. The effect is like looking at 500 postcards.

With about 1,000 copies sold since it went on sale in December, the book seems to have stirred a lot of memories, Andrews said. “We've been really impressed with the number of people who have identified with the buildings,” he said. “They'll come up to us and say they recognized a building, or that they grew up in a building in the book—some personal attachment that makes the book very meaningful to them.”

First of its kind

Perhaps the most striking thing about the work—considering Hartford is more than 350 years old—is that no one had published anything like it before. “Many cities have a book of this character, so the void in Hartford was fairly obvious,” Ransom said.

“It was something that each of us had thought about for a long time,” said Andrews, a lawyer turned architectural historian. The real spur for the book, he said, came when a friend visited from Washington D.C. “She said, ‘Where's the book on Hartford architecture?’” he recalled. “We had to admit there wasn't one but that we'd fill the gap as soon as possible.”

As veteran preservationists, Andrews and Ransom already knew many of the buildings that would eventually wind up in the book. “It's the sort of information you accumulate over a period of years,” Ransom said.

“I don't think you could just go into a town and write a book like this in two or three years—which is how long it took us to write this one,” he added.

Photographing 500 structures and writing about them takes time and money. The Hartford Foundation for Public Giving and the Howard and Bush Foundation helped supply the first in the form of grants, but neither the authors nor the historical society will make any money on the book.

“The historical society will be out of pocket on the deal, and I think that is a contributing factor of why it hasn't been done before,” Ransom said.

11 neighborhood tours

Once they started working on the book, Andrews and Ransom divided the city into 11 neighborhoods, so readers could take tours of each one. “Then each of us went around driving, looking as carefully as we could, to choose the 40 or 50 buildings that we thought would be appropriate and representative for a tour,” Andrews said.

Fine architecture wasn't the only criteria for deciding which buildings got into the book. “We also tried to pick the buildings that we thought were significant to the history of the city,” Ransom said. “We tried to pick a range of styles, a range of building types, and a range of locations.”

“Certainly, many buildings that don't look like palaces can have considerable architectural and historic interest,” he added.

Examples of that, Ransom said, are what's left of the workers' housing built in the Parkville section of town during the late 1800s. “These houses are not handsome, but they represent a row of workers' housing, which is what that community was about back then.”

Andrews and Ransom outline Hartford's architectural history in a narrative chapter at the end of the book, showing how the city's changing architectural styles reflected the economic, social and technological forces that swept through it. They note, for instance, that the Old State House faces the Connecticut River, not Main Street—an indication of how heavily colonial Hartford relied on river commerce.

Unfortunately, the Old State House is one of few buildings left from Hartford's earliest days, Andrews said. “I think it's fair to say that Hartford is comparable with other cities in quality and kinds of buildings, but it perhaps has fewer 18th-century buildings than many other cities of its size and age in the Northeast,” he said.

One reason for that, Andrews said, is that there weren't many buildings back then to begin with. “Hartford in the 18th century was a comparatively small place—smaller than such cities as Newport,” he said.

Also, Ransom said, colonial Hartford was doomed by its own success as well as its location along the riverfront; the early cluster of houses eventually became the downtown business district, so the old houses were replaced.

“One thing Hartford is fortunate in having is a wealth of 19th-century brick buildings—probably, I think, more than other city in the Northeast, because it grew up so much in the 19th century,” Andrews said. Examples of it, he added, are the rows of apartment buildings constructed for factory workers in the Frog Hollow section, which includes Capital Avenue and Park Street.

Looking toward future

Despite its historical emphasis, “Structures and Styles” is anything but musty. The current downtown office boom, though still on the drawing boards in some cases, leaves a big imprint on the book. CityPlace, State House Square and other towers built downtown over the past 10 years receive treatment, and the narrative chapter at the end contains a diagram of the proposed 59-story Cutter Financial Center.

Andrews and Ransom give the boom decidedly mixed reviews, however. They note in the book that it includes no new apartment buildings and that the city's retail sector “has achieved a tenuous stability,” always under threat of replacement by office space.

And of course, there is the threat to architecturally significant older buildings. For example, preservationists fought to save the 19th-century Goodwin Building, but the developers of a proposed office building and hotel on the site agreed in the end to incorporate only its facade into the new building's design. “That its highly ornate facade was saved, while the fine interior was destroyed, was a hollow victory,” Andrews and Ransom write.

One good side effect of the office boom—from a preservationist's point of view—is a growing appreciation for the remaining older buildings throughout the city, Andrews said.

The best example of that, he said, is the state Capitol. “The state has spent a lot of money to restore it to its original glory,” he said, recalling that its architectural style once provoked “dismay and dislike” among many people.

“It was old-fashioned, out of style, fussy,” Ransom said. “There wasn't a good word to be said for it.”

“A lot of people called it Disneyland North,” Andrews remarked, adding that it since seems to have come back into favor.

Despite some disappointments, today's downtown boom seems more tempered by concern for preserving significant older buildings than the redevelopment drive of the 1950s and 1960s, Ransom and Andrews said.

That period saw the construction of interstates 91 and 84, the latter claiming the Gothic old Hartford Public High School on Hopkins Street. Also, the dilapidated East End disappeared beneath Constitution Plaza and I-91, taking with it what Andrews called “a wealth of old buildings.”

“At that time, Hartford needed revitalizing, economically,” Ransom said. “I guess we feel that the revitalizing could have been done a little more sensitively, with a mixture of good old buildings and new ones.”

“Let's say that the city is much more sensitive than it used to be and that there is a greater awareness about the need to save historically and architecturally significant buildings,” Andrews said.“The role of the Greater Hartford Architecture Conservancy has been vital in that.”

“At least now there's some dialogue,” Ransom added. “We don't always win, but at least there are some discussions.”

Editor's notes: 2 Amid the recession of the early 1990s, plans for the Cutter Financial Center were shelved. 3 The architecture conservancy filed for bankruptcy in 1997; it has been succeeded by the Hartford Preservation Alliance.